An article recently published by the Wildlife Unit of the University of Aveiro, in partnership with Rewilding Portugal and Zoological (Lino et al., 2023), which includes data collected as part of the LIFE WolFlux project, highlights the impact of predation by stray dogs on livestock and reveals a greater representation of wild ungulates in the diet of the Iberian wolf south of the Douro River.

Stray dogs, a growing problem in Portugal and Europe

The growing (and uncontrolled) increase in stray dogs, especially in rural regions across Europe, has created new challenges that need a quick and assertive response based on concrete data, such as the ones presented in this article.

In relation to predation on domestic livestock, these kinds of cases reported are common throughout Europe, particularly in Sweden, Estonia, Poland, Italy and even our neighbor Spain. This is just one of the major problems that can arise from the increased presence of stray dogs in the landscape and on wolf lands, as other problems have also been identified: predation on wild species, often in direct competition with the wolf (e.g. roe deer, wild boar and red deer); the spread of diseases among carnivores; and the possibility of hybridization with wolves.

In Portugal, the abundance of the Iberian wolf (Canis lupus signatus) declined dramatically during the 20th century, mainly due to human persecution and habitat loss. Currently, it only occurs in 20% of its original distribution area, and although it has been a legally protected species in Portugal since 1988, it is still listed as “Endangered” in the Red Book of Mammals of Portugal.

For example, in 2016, official pet rescue centers recovered more than 4,000 dogs only in central Portugal. However, the scale of the number of stray dogs remains unknown. Many of these animals are abandoned hunting and pet dogs. Others are owned dogs which, due to their role in human activities (e.g. livestock dogs), are allowed to roam freely. However, many other owned dogs with no specific function to justify it also enjoy this freedom of movement, which makes these cases even more likely (Espírito-Santo 2007). Despite the high number of dogs in areas where wolves are present, there is no published quantitative data on their prey consumption patterns in Portugal.

The article recently published by the Wildlife Unit of University of Aveiro, in collaboration with Rewilding Portugal and Zoological (“Dog in sheep’s clothing: livestock depredation by free‑ranging dogs may pose new challenges to wolf conservation”, Lino et al., 2023) evaluates and compares the diet composition of wolves and stray dogs in the distribution area of the wolf south of the Douro River, the most endangered subpopulation in Portugal.

Results, conclusions and future steps

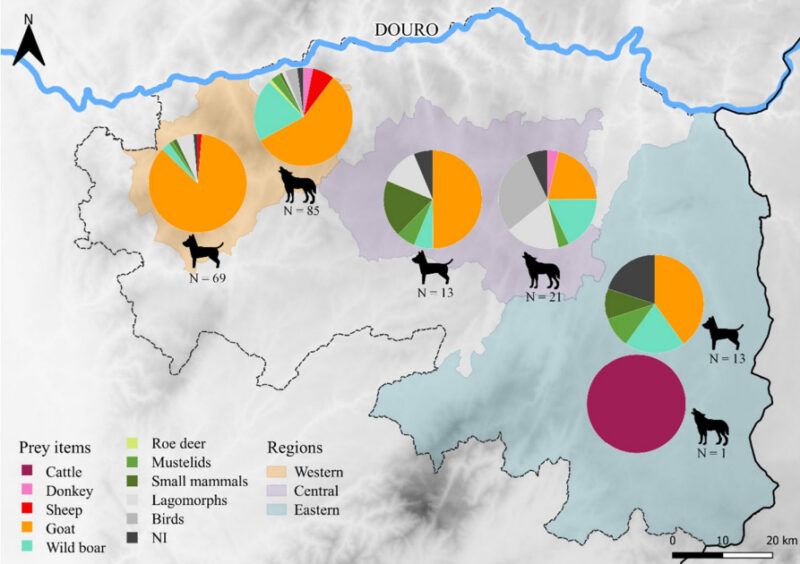

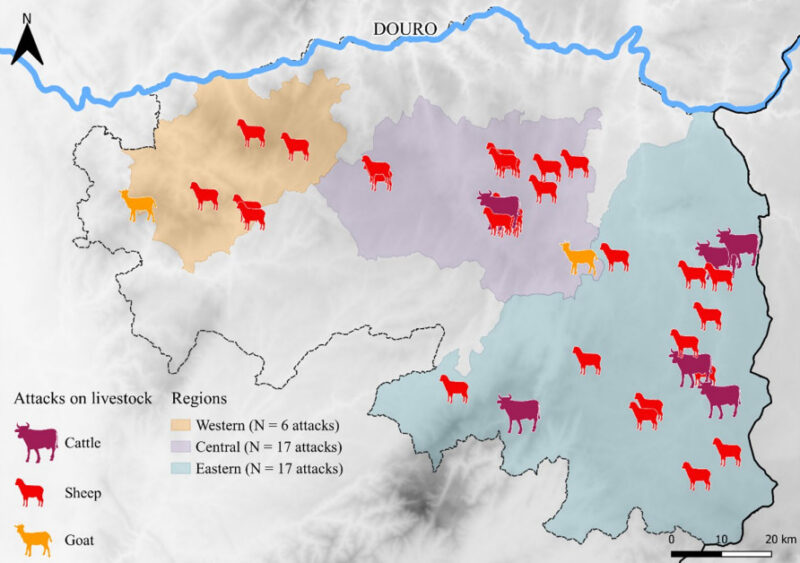

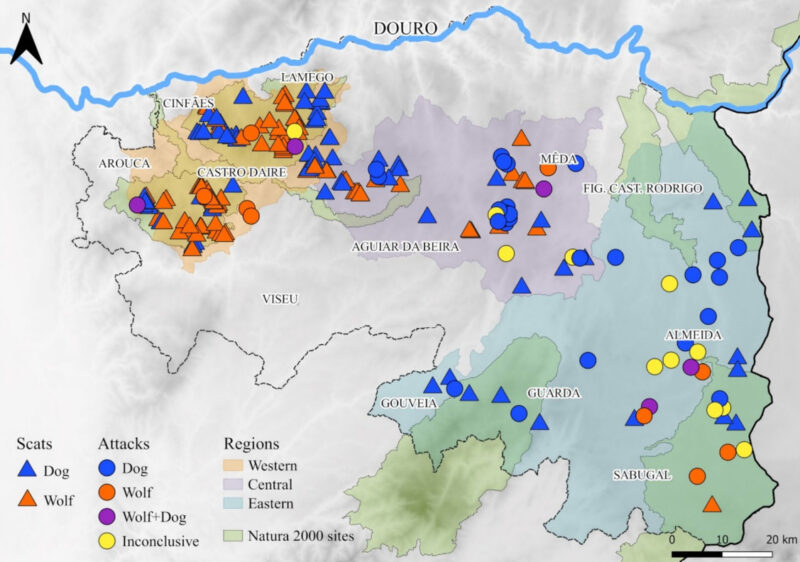

The study includes samples from the entire length of the wolf’s distribution area south of the River Douro, namely two Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) defined in the Natura 2000 Network Sector Plan, namely “Serras da Freita e Arada” (PTCON0047) and “Montemuro” (PTCON00025). This mountainous region, with altitudes of up to 1381m, covers the range of three confirmed wolf packs (Arada, Cinfães and Montemuro). To carry it out, 107 wolf scats and 95 genetically confirmed dog scats were analyzed. In addition, 40 attacks on livestock were considered, with genetic confirmation of the species that fed on the carcasses of the predated animals.

This analysis of scats highlighted goats as the prey most consumed by dogs in all the regions analyzed, followed by lagomorphs (rabbits and hares), small mammals and wild boar. Wolves feed mainly on goats and wild boar in the west, while in the central region they feed mainly on birds, and it is likely that this high consumption comes from animal carcasses that are discarded by farms in the area. Diet overlap between the two canids was very high, demonstrating a high potential for competition for resources.

In addition, it was found that dogs were the only predators detected in the majority of attacks (62%), a surprising finding that reveals the highly influential role they may play in exacerbating conflicts between local communities and the Iberian wolf, since the wolf is often presumed to be the perpetrator of attacks by default. The results therefore highlight the role of dogs as possible predators of livestock and possibly also of wild species. In addition to appropriate management practices, we stress the need for stricter enforcement of legislation on dog ownership and effective management of the wandering population to reduce conflicts between humans and wolves.

Progress towards rewilding and damage prevention

This study also led to the conclusion that the composition of the wolf’s diet is more diverse than previously described for the Western Southern Douro region, with the consumption of wild boar and roe deer representing a greater proportion of the species’ diet when compared to previous assessments. This represents an important success result for conservation, as it is the result not only of the natural expansion of wild boar and roe deer, but also of conservation programs of roe deer reintroduction (Torres et al. 2018) and the increase of damage preventive measures supported by various programs and wolf conservation projects, including LIFE WolFlux. An excellent result since, for decades, the only prey the wolf had south of the Douro were cattle, as its natural, wild prey had become extinct.

At the time of writing, Rewilding Portugal has delivered 96 livestock dogs and 34 fences to prevent and reduce wolf attacks throughout the species’ range south of the Douro River. It also works to restore and protect the habitat of the wolf’s prey in conjunction with local actors, and is currently carrying out work to restore native forests and pastures on 50 hectares, create 20 new water points for wildlife and work in collaboration with hunting associations to implement sustainable Global Wildlife Management Plans and hunting refuge areas on more than 700 hectares.